I still remember that coffee machine[1]. I recall how we used to stay up in the university computer lab, often until late at night, fascinated in front of its image while immersed in the ghostly glare of some black and white Mac SE/30 screen monitors. We repeatedly refreshed our Mosaic window in the tantalizing hope of catching the glimpse of a hand reaching for the pot in that distant lab in Cambridge. Suddenly, all distances seemed annihilated. We were in a small computer lab of a minor Swiss university, but we were also in Cambridge at the very same time.

This is my first vivid memory of that shining new thing called the World Wide Web, or WWW or even W3 for short. But it certainly isn't my first memory of connecting to the larger Internet and discovering a new kind of wonder and excitement there. Oh yes: and also a vast, useful source of information... After all, we were supposed to study and research, weren't we?

I first went online just in time to learn about BBSes, and used to irregularly visit some of them. I have vague but fond memories of a quirky world of servers, each one with its own distinct personality. But, although we did connect to them (and on some we could even play and compete in games), to me there was always something about them that felt asynchronous. In the end, it wouldn't be BBSes that gave me that first spark of understanding of what synchronous networking all over the world really could be.

Usenet's newsgroups were very much more the thing for me. Not only were they good fun to participate in, but they were also actually useful for my studies. There, I could ask a question about a quite specific topic and have a very good chance to see it answered by a specialist of the field, even if that person was living on the other side of the world. I also had a couple of short exchanges with some book authors I admired very much: how fantastic was that? I never would have had the chance to meet those people otherwise than virtually!

Usenet felt much less isolated than BBSes. This was the cyberworld where I got my first glimpse of what an online community could be, with its subcultures, a specific terminology, cryptic references to its own historical events (the "Great Renaming," or the yet-to-come "Eternal September") and so on.

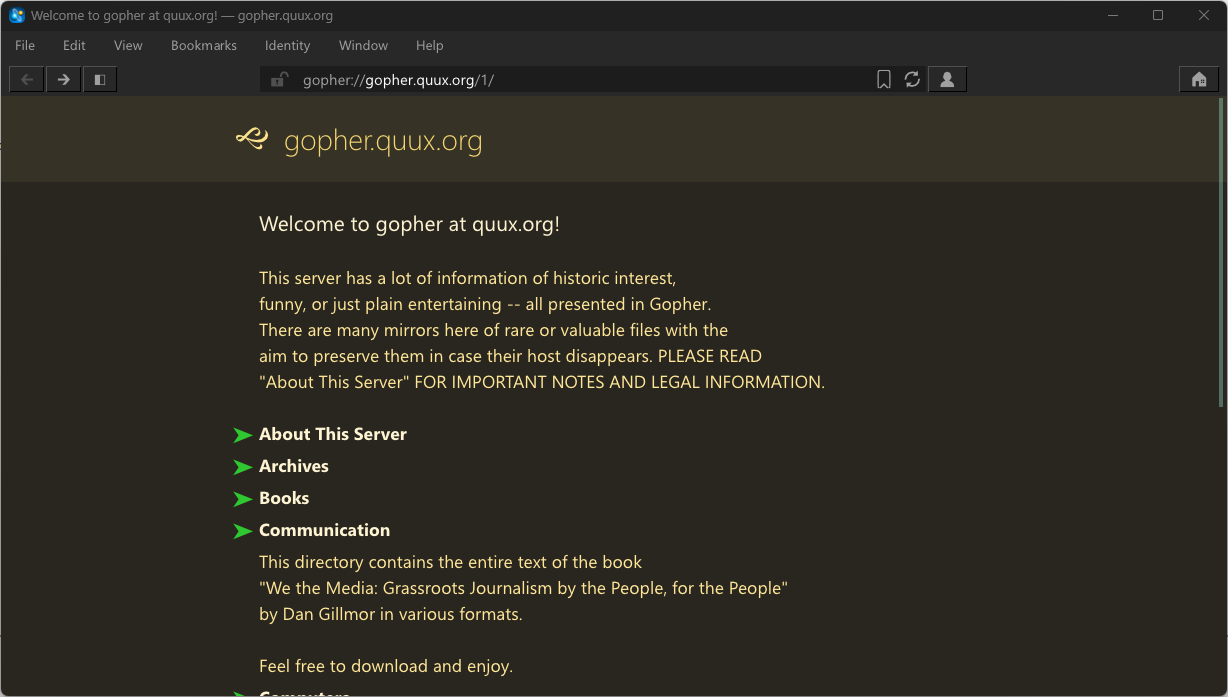

But what really blew my mind open to the Cyberspace was Gopher. Burrowing through Gopherspace made me discover a seemingly infinite world of possibilities. And thanks to our university servers, I could even try my hand at putting things on there myself. For the first time I, an avid reader, discovered the power of self-publication! What a change of world-view that was. All that time passed on Gopher space certainly did not seem like wasted time to me: so much knowledge to be gained, so many discoveries to be made... Magical times indeed!

It is probably difficult to comprehend this nowadays, but you should understand that Gopher truly could have been so much more at the time. This protocol potential was such that I recall that at one time almost nobody knew about the WWW, but even outside academia some press articles wrote about Gopher as "the best way to access the Internet"! Well... We all know how that went since then, don't we?

Perhaps being in academia made us see Gopher as much more important than it was destined to be. To be fair the protocol itself, even with all its quirks and limitations, wasn't really at fault per se. Some unfortunate political decisions taken by the university where Gopher was developed are much more to blame. Even Sir Tim Berners-Lee underlined this point in his book "Weaving the Web," published in 1999 (pp. 72-73):

"It was just about this time, spring 1993, that the University of Minnesota decided that it would ask for a license fee from certain classes of users who wanted to use gopher. Since the gopher software was being picked up so widely, the university was going to charge an annual fee. The browser, and the act of browsing, would be free, and the server software would remain free to nonprofit and educational institutions. But any other users, notably companies, would have to pay to use gopher server software.

This was an act of treason in the academic community and the Internet community. Even if the university never charged anyone a dime, the fact that the school had announced it was reserving the right to charge people for the use of the gopher protocols meant it had crossed the line. To use the technology was too risky. Industry dropped gopher like a hot potato."

Also in 1993, the US National Center for Supercomputing Applications would release NCSA Mosaic, the first World Wide Web browser with a graphical interface, and from that moment on for the Gopher protocol the writing pretty much was on the wall. Part of the Web initial success was indeed thanks to the images, that Mosaic could show inline, like that memorable coffeepot. One could almost say this was W3's first killer app. On Gopher, you could certainly download and then view images or hear music files on your computer, but it was essentially a world of text at its core.

Let's be honest, though: it wasn't only images or the prospect of fees that decided the supremacy of W3 over Gopher. The World Wide Web was also mind-blowing in its own right! Learning HTML by viewing the source of other's webpages to see how they did things was lots of fun, if you were so predisposed, and being able to publish a Personal Webpage by simply using a text editor and an FTP program was truly empowering. I too would eventually take to it like a duck to water. "This is for everyone" indeed!

But now? Well, the Web just turned 34 and since its idealistic beginnings and exponential explosion in adoption it has also become ever so smaller, reduced to a handful of online powerhouse walled gardens, harvesting clicks and likes... Yes, you as a Good Internet reader know that web of yore we thought lost was still here all along, but sadly for a vast majority of users this is not what they associate with the web anymore. For all practical purposes, to them those attention-grabbing walled gardens sadly are the web.

Meanwhile Gopher has proved to be surprisingly resilient, against all expectations. It still exists out there, and it even knows a kind of revival in the IndieWeb community. Yes, it is a quirky and loose protocol, it may be not up to snuff with modern security practices, but listen: it just works! You can even access it via that awesome, modern retro 8-bit machine that is the ZX Spectrum Next.

Yes, Gopher indeed is still relevant, to the point of at least partially inspiring another more modern protocol: Gemini. And lately, after watching for decades its numbers slowly but steadily dwindle, I see new Gopherholes (the equivalent of websites on Gopher) joyfully popping up again all over the place. Perhaps this positive trend is also helped by the younger generation newly-found interest in Geminispace? Who knows, but it certainly is a heartening sight!

Gopher's no-nonsense simplicity, with all its limitations and weirdness coming from another simpler era, still has a lot to offer. Its plainness brings clarity. It is almost trivial to find what you're looking for on Gopher: after all, it was made for serving files. This is its whole raison d'être, if you will.

Gopher is also easy and fun. The simplicity of its protocol makes it an ideal toy to tinker with, and although they tend to remain simple hobby projects, I see a lot of enthusiasts cutting their first teeth in development by writing a gopher client, or even a server. It is far more simple than writing a web browser from scratch, for instance.

As for an even simpler goal, putting your own Gopherhole online is dead easy. All Gopher menus are simple, plain text files formatted in an admittedly rather rigid format. You don't need to worry about looks, you truly can focus yourself on your contents and on how to organise them. There is even the equivalent of blogs in Gopherspace: they're called phlogs and you can find scripts around (or write your own) to help you managing them. Although you could also do this by hand very easily by editing and uploading some simple text files.

Most of all, Gopher is a peaceful, simpler place. In our day and age this counts for something. No attention-grabbing, constant updates, no video autoplay or hidden content behind mandatory account creation or paywalls, no trackers or beacons chipping away at whatever little remains of your privacy... Forget about your everyday walled-garden web variety fatigue!

Please, understand that I'm not arguing the superiority of Gopher over WWW here. I've seen enough of the first Browser Wars for not wanting another Protocol War. The Web still has its own strengths, and Gopher has a number of weaknesses too. For one, it requires you to be more savvy about what you're doing, both as a user and as a publisher; there is no indication that a Gopher link truly brings you where it says it does, for instance. As we used to say back in the days: you should always practice safe hex.

We do not live in a Manichaean world (regardless of what a vocal minority would love us to believe) where only one protocol is "The Chosen Holder of the Truth." I think, on the contrary, that the World Wide Web and Gopher (and Gemini too) can and should coexist, because they complement and complete each other. If anything, by rediscovering Gopher, one may also rethink its approach to the Web and reconsider what is so precious about the simple idea of making information freely available and connecting us to each other, what is so revolutionary about the power of online self-publication. Both Gopher and the Web at their best give you the power to be your own Gutenberg!

If you want to see by yourself what it's all about, there are still a number of Gopher clients out there that will allow you to do so. The Lynx browser, for one, is one of the rare (text) web browsers still supporting Gopher, and the dedicated Gophie can run on any OS which supports Java. Even the Gemini client Lagrange supports Gopher, although in a simpler, pared-down manner. When you're online, there is a search engine called Veronica-2 and a portal of sorts at Floodgap Systems. These are all good starting points for you to explore Gopherspace.

And if you want to try to dig your own Gopherhole, Gopher servers that are still maintained do exist. Updates may not be frequent (it is after all a rather mature protocol), but you have quite a lot of them to choose from: the excellently-named Gophernicus, for instance, or the multi-protocol PyGopherd which can also serve an HyperText version of the contents of your Gopherhole, to name just two of them. And if you wish to publish a Website and a Gopherhole at the same time, the marvellous kiki, "a tiny homepage construction kit with a small footprint" by vga256, can now even automatically output gophermaps with your content ("Bring Your Own Gopher Daemon," though)!

If you haven't already, I strongly encourage you to give Gopher a try. You will soon notice that this old protocol is still oh so remarkably modern. You'll see: in no time, you'll dig it too!

Serge Keller is a scientific journalist and a cordial communicator. He used to be a biologist, and before that a zoo keeper, and to this day he has kept a strong interest in natural sciences. He currently lives between Switzerland and Italy (yes, it's somewhat complicated...) and can speak, write, read (and sometimes think) in Italian, French, English or German. He still very occasionally writes on Almaren on the Web and is currently reviving Port70.ch on Gopher.

For more information, see Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trojan_Room_coffee_pot ↩︎

Member comments